Banner: Griffin Cork and Yoshie Bancroft; projection design by Cindy Mochizuki; photo by David Cooper.

Adapted from the Nikkei National Museum exhibits Taiken and Hastings Park 1942 as a companion to the Arts Club Theatre Company’s 2023 production of Forgiveness.

バナー:グリフィン・コークとヨシエ・バンクロフト(プロジェクション・デザイナー:シンディー・モチヅキ、写真:デイビッド・クーパー)

このページは、1月12日から2月12日までスタンレー・インダストリアル・アライアンス・ステージにて開催される、アートクラブ・シアター・カンパニーによる2023年制作の舞台「Forgiveness」の案内書として、日系博物館の「体験」展と「ヘイスティングスパーク1942」展をもとに作成されました。

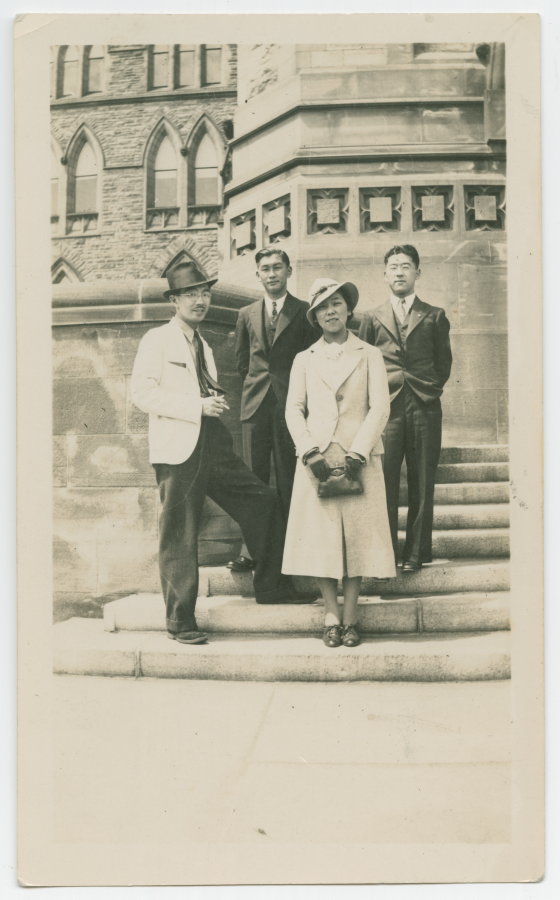

Hide Hyodo (third from left) was the only Japanese Canadian to be hired as a public school teacher in BC in the prewar era. Other qualified Japanese Canadians had to relocate or change professions.

Isami (Sam) Okamoto fonds. 2000.14.1.1.1

男性3人と女性1人が、オンタリオ州オタワの国会議事堂入り口の階段に立っている。左から、サミュエル・I・ハヤカワ、ミノル・コバヤシ、ヒデ・シミズ(旧姓ヒョウドウ)、エドワード・バンノ。ヒデ・ヒョウドウ(左から3人目)は、戦前BC州で公立の学校の教師として雇われた唯一の日系カナダ人だった。

Acts of Injustice

The first recorded immigrants from Japan began to arrive in what we call Canada in the late 1800s. The lands they came to had been cared for by Indigenous peoples for thousands of years. Japanese immigrants arrived soon after Britain colonized these lands.

As seen in Forgiveness, Japanese Canadians faced lots of racial discrimination in Canada. Even Canadian-born citizens of Japanese ancestry were not allowed to vote. Japanese Canadians and other racialized workers were paid less than white workers for doing the same jobs. Laws banned Japanese Canadians from certain jobs. And there were many more jobs that would not hire Japanese Canadians, even if they were qualified.

Canada’s racism became even worse when the country declared war on Japan in 1941. The government used Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor as an excuse to violate Japanese Canadians’ rights. Even though most Japanese Canadians had been born in Canada or had become naturalized Canadian citizens, the government called them all “persons of Japanese racial origin”, ignoring citizenship status.

Leaders of the RCMP and the military said that Japanese Canadians were not a threat to Canada’s security. But the government ignored them. They ordered Japanese Canadians to leave their homes and communities.

不当な扱い

今私たちがカナダと呼ぶこの土地に、日本から最初に移り住んだ移民の記録は、1800年代の後半に遡る。彼らがやってきた土地は何千年もの間、先住民族が大切にしてきた土地だった。日本からの移民が始まったのは、英国がこれらの土地を植民地化してまもなくのことだった。

「Forgiveness」で演じられているように、日系カナダ人はカナダで多くの人種差別に直面した。カナダ生まれのカナダ国民であっても、日本人を先祖として持つ者には選挙権が与えられなかった。日系カナダ人をはじめ、差別を受けている人種の労働者たちは、同じ仕事をしている白人より少ない給料しか与えられなかった。日系カナダ人の就業が法によって禁じられている職業があり、また就業資格をもっていたとしても日系カナダ人は雇いたがらない職場も多かった。

1941年にカナダと日本が開戦すると、人種差別は更に激しくなった。カナダ政府は、日本のパールハーバー攻撃を日系人の権利を侵害するための言い訳に利用した。日系人のほとんどはカナダ生まれであったり、帰化してカナダ国民になっていたにも関わらず、カナダ政府は日系人のことを「日本に人種的起源をもつ者」と呼んだ。カナダ国民であるという事実は全く考慮されなかったのである。カナダ連邦警察(RCMP)や軍の指導者たちは、日系カナダ人はカナダの安全を脅かすことはないといったが、カナダ政府はこを無視した。日系人は住んでいる家やコミュニティーからの退去を命じられた。

Hastings Park

In early 1942, the Pacific National Exhibition (PNE) grounds at Hastings Park in east Vancouver were used to temporarily house Japanese Canadians like Mitsue and her family who were being uprooted from the BC Coast. Over 8000 were detained in the exhibition buildings and stables at Hastings Park before being sent to internment sites in the BC interior or to work camps across the country.

For many Japanese Canadians, this was a terrible, fearful experience. They were forcibly removed from their homes, lost all of their belongings and many families were separated. The conditions at Hastings Park were extremely primitive and unsanitary. The primary memory for many people was the horrible smell, followed by the noise, the boredom and the terrible food.

In 2015, four commemorative plaques were unveiled at sites around Hastings Park. The Japanese Canadian Hastings Park Interpretive Centre Society is currently developing plans for an interpretive centre at Hastings Park to commemorate this history and the people incarcerated there.

Below: An image of interior of building with many bunk beds. Photographer: Leonard Frank. Alex Eastwood collection. 1994.69.3.18

ヘイスティングスパーク

1942年初頭、バンクーバー東部にあるヘイスティングスパーク内、パシフィック・ナショナル・エキシビション(PNE)は、ミツエたち家族のように、BC州の沿岸部から強制退去させられた日系カナダ人たちを一時的に収容する場所として使用された。8000人を超える日系人が、展示場の建物やヘイスティングスパークの馬小屋に収容され、BC州内陸部の収容所かカナダ各地の労働キャンプに送られるのを待った。

多くの日系カナダ人にとって、それは辛く恐ろしい経験だった。住んでいた家から追い出され、持っていたものをすべて失った。また多くの人が家族と離れ離れにされた。ヘイスティングスパークは、極めて原始的で不衛生な状態だった。多くの人がまず覚えているのは強烈な悪臭だったが、加えて騒音はひどく、人々は退屈し、食べ物もひどかった。

2015年、ヘイスティングスパーク内の4か所に記念の銘板が建てられた。日系カナダ人ヘイスティングスパーク情報センター協会(Japanese Canadian Hastings Park Interpretive Centre Society)では現在、この強制収容の歴史と収容された人々を記憶するため、ヘイスティングスパークに情報センターを建設する計画を進めている。

下の写真:たくさんの二段ベッドが並ぶ建物内。写真:レオナルド・フランク Alex Eastwood collection. 1994.69.3.18

Life in the Internment Era (1942-1949)

Japanese Canadians built community in harsh and isolated conditions. In internment camps, they lived in small, quickly built shacks. They had no insulation, running water, or electricity. Many had to share living quarters with another family.

Most had little or no choice about where they lived. The government separated men from their families. Sometimes families didn’t know where their relatives were sent to for months. On sugar beet farms, everyone old enough to work spent long hours in the fields.

Even while imprisoned in internment camps, Japanese Canadians tried to make their new communities better. They set up schools, churches, and activities. They grew food in gardens when they couldn’t buy enough in stores. Young adults volunteered to teach school and coach baseball teams.

Legacies

The struggle for redress took many years. Throughout the 1980s in particular, Japanese Canadians worked hard to educate all Canadians about the internment era. Many asked whether anything could truly make up for all we had lost and endured.

A redress settlement was announced in Parliament on September 22, 1988. It included:

- an acknowledgment that Canada had violated Japanese Canadians’ human rights

- individual payments of $21,000 to survivors of these violations

- the establishment of a Japanese Canadian community fund of $12 million

- the clearing of criminal records for those charged under the War Measures Act

- restoration of Canadian citizenship to those exiled to Japan

- the creation of the Canadian Race Relations Foundation to help eliminate racism.

The 1988 redress settlement was negotiated between the National Association of Japanese Canadians and the federal government. In 2012, MLA Naomi Yamamoto, the first Japanese Canadian to be elected to the BC Legislature, led a Motion of Apology to the Japanese Canadians in the BC Legislature. This began another redress movement which led to a negotiation process to acknowledge and redress the BC provincial government’s role in Japanese Canadian internment. Premier John Horgan announced a provincial redress settlement in May 2022.

Below: Prime Minister Brian Mulroney shakes hands with NAJC president Art Miki after they sign the redress agreement on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, Ontario, 1988. Photographer: Gordon King. NNM 2010.32.29

強制収容期(1942~1949年)の生活

日系カナダ人は、厳しい孤立した環境の中でコミュニティーを築いた。強制収容所では、急ごしらえの小さい粗末な小屋に住み、断熱材や電気、水道のない暮らしを強いられた。また多くの人は、一つの小屋を別の家族と分け合って暮らした。

ほとんどの人は住む場所を選ぶことが出来ず、できたとしても選択肢はほとんどなかった。またカナダ政府は、男性を家族から引き離した。自分の家族、親戚がどこにいるのか、何か月もわからないこともあった。砂糖大根(甜菜)農場では、働ける年齢の者は皆、何時間も畑で働いた。

強制収容所に入れられている間も日系人たちは、自分たちが暮らす新しいコミュニティーをより良くしようと努めた。学校や教会を作り、様々な活動を行った。十分な食物が店で買えない時には、庭で野菜や家畜を育てた。若者たちはすすんで学校で子供たちを教え、野球チームでコーチをした。

遺産

リドレス(政府による公式謝罪と補償)への闘いは何年もの歳月を要した。特に1980年代を通して日系カナダ人は、すべてのカナダ人に強制収容期の出来事を知ってもらえるよう努力を重ねた。多くのカナダ人が、日系人が失ったものや耐え忍んだ苦痛を償うためにできることはないのかを問うた。

1988年9月22日、リドレス合意が連邦議会で発表された。合意書には次の内容が含まれた。

- カナダが日系カナダ人の人権を侵害したことを認めること

- 損害を受けた個人に対して一人2万1千ドルを支払うこと

- 日系カナダ人コミュニティーのための基金設立に1千2百万ドル支給すること

- 戦時措置法により犯罪者とされた人々の犯罪歴を抹消すること

- 日本へ追放された人々のカナダ国籍を回復すること

- 人種差別撲滅に役立てるため、カナダ人種関係基金を設立すること

1988年のリドレス合意は、全カナダ日系人協会とカナダ政府との間の交渉の末に成立した。BC州議会で選出された初めての日系カナダ人ナオミ・ヤマモト議員は2012年、BC州議会で日系カナダ人に対して謝罪を行うという動議を先導しました。これが新たなリドレス運動となり、BC州政府が日系人の強制収容において果たした役割について認め補償することを求める交渉へとつながりました。ジョン・ホーガンBC州首相は2022年5月、州のレドレス合意を発表しました。

下の写真: 1988年オンタリオ州オタワの国会議事堂でリドレス合意署名後に握手をする、ブライアン・マルルーニ首相とNAJC会長のアート・ミキ。写真:ゴードン・キング NNM 2010.32.29

Find out more

To learn more about the history and heritage of Japanese Canadians:

- Visit the Taiken: Generations of Resilience exhibit at the Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Centre in Burnaby, BC.

- Visit the Nikkei National Museum website and our online exhibits and educational resources, including the Hastings Park 1942 online exhibit.

- Visit Hastings Park and look for the four green interpretive panels near historic buildings.

- Check out this great resource about the Celtic Cannery neighbourhood by the Vancouver Heritage Foundation.

さらに詳しく知るには

日系カナダ人の歴史や遺産について更に詳しく学びたい方は、以下をご覧ください。

- 日系文化センター・博物館(BC州バーナビー)内の常設展示「体験(Taiken: Generations of Resilience)」

- 日系博物館のウェブサイトや「ヘイスティングスパーク1942」などのオンライン展示と学習用資料

- ヘイスティングスパーク内の歴史的建造物近く4か所に設置されている緑色の解説パネル